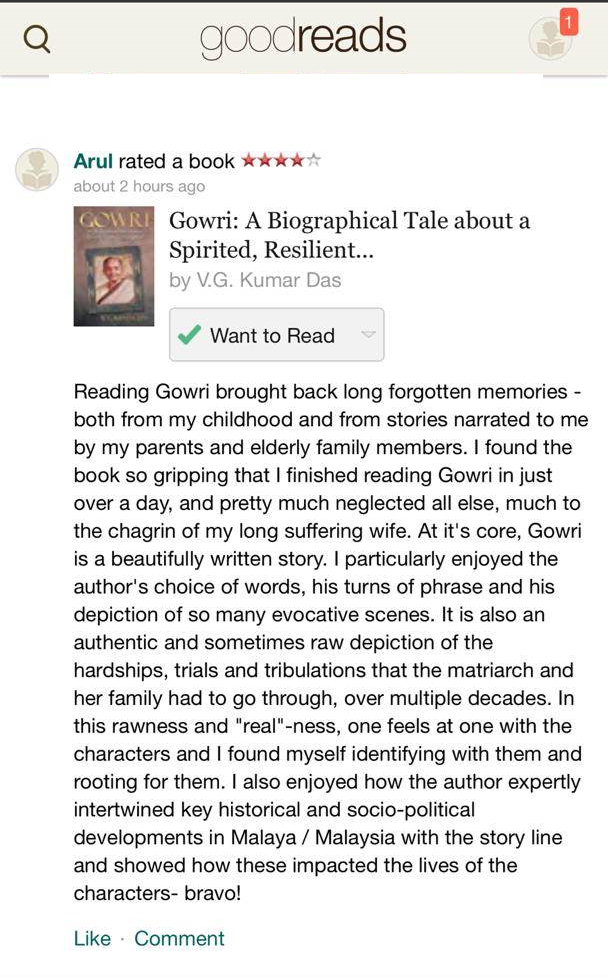

The book’s limitation in not being able to bare it all is understandable, particularly when one is writing about a family history in the context of colonial expansion, administration and decolonization with which its own history has been coterminous. This calls for meticulous balance. Also, any family in that situation must have faced enormous challenges brought about by the struggle to survive. These usually entail squabbles and disputes and also a number of successes and failures where some win and others get relegated to the margins of existence. Most Indians have faced similar experiences in the Indian Diaspora and have elevated their status by sending their children ‘overseas’ for studies. Often, this implies the United Kingdom, the main colonial power under whose sovereignty most overseas Indians lived. For British Malaya, this term included Australia, whose proximity made it more attractive than colder and more ‘alien’ destinations such as Canada and the USA. In this context, the author, despite, or because of, his family circumstances, was able to go for further studies to Australia and ended up as Chair of Inorganic Chemistry and Dean at the Faculty of Sciences at the University of Malaya. He also became a Vice Chancellor and Chief Executive of two universities in the country – Kedah and Perak – both of which he founded.

For Malaysian Indian readers, the story may be commonplace and could be dismissed as being self-serving. For Diasporic Indians, there are insights to glean, even though the writer may not have intended these. As Roland Barthes suggests in his ‘Death of the Author’ that when an author finishes writing a book, he ‘dies’ and the book takes on a new dimension in the mind of the reader, I have taken the liberty as a reader to ‘rewrite’ the book from a Diasporic Indian perspective to show that there is much to learn from this book through the sharing of family narratives.

Firstly, the story reflects the tenacity of the Indian mother, bringing up her children in a foreign country trying to juggle with four or more cultures coupled with all the challenges posed by acculturation. Gowri does this on her own terms, stressing to her prospective Christian daughter in law not to religiously convert her son from Hinduism to Christianity but assuring her that she will not insist on the same for her daughter in law’s children. Here, she was embracing, ahead of her time, the new reality of today’s families which are biracial, binational, bicultural and, in some cases, even bi religious. She accepts her daughter in law into the family with open hearted magnanimity and christens her “‘Shanti’ which means ‘peace’ – something so desperately needed today at all levels of society.

Secondly, the book highlights the role education played in the survival and upward mobility of the Diasporic Indians. ‘This is nothing new’ as many Indians would say, but sufficient enough to strike a resonant chord in the hearts of many Diasporic Indians who, like the Indians of Malaysia, have produced some outstanding people who are playing an important role in civil society in many of the countries where they are settled today (see Planet India by Mira Kamdar to gain an insight on the part played by overseas Indians in the USA). While this is true of many immigrant communities across the world, what is important for Diasporic Indians, referred to by Yash Tandon as ‘stepchildren of the colonial empire’, is the salutary message that education has been, and continues to remain, their greatest asset.

Thirdly, and purely for historic reasons – and many may ask ‘who reads history these days?’ – is the story of the struggle for the emancipation of India. While not much is really known of the early struggle of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi in South Africa and how the emancipation of India had its seeds in South Africa, not much is known of the struggle of Subhas Chandra Bose and his struggle in Malaya against British colonialism by flirting with the occupying Japanese power in British Malaya. While Das’ book does not dwell at any length on this part of colonial history – and understandably so being a family memoir – it does give an insight on what colonial Indians had to grapple with in their long journey towards their own emancipation as well as that of India’s.

Lastly, and most importantly, the book shows the role minorities played in post-colonial societies where massive reconstruction of society was called for in many parts of the world. While this may have passed as a phenomenon associated with the dying embers of colonialism, it does raise its ugly head today in ongoing debates revolving around contemporary issues such as mass migrations, greater acceptance of diversity and how a country can meaningfully embrace pluralism. A better understanding of the past helps to engender a culture of live and let live. The book, from its reading, does touch on the race riots of 1969 in Malaysia but not in any depth about its long-term implications in a country where race is now progressively being conflated with religion as an important determinant of identity and therefore about belonging. Perhaps here, a better understanding of the overseas Indians’ own narratives, albeit by way of family chronicles couched in a ‘down memory lane’ language, do provide deep insights of what mattered to people and how their humble contributions went to make up the pluralistic societies that constitute many of the nation states of today – a reality to come to serious terms with though denied by many. In Milan Kundera’s words ‘the struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting’. Narratives such as Gowri, no doubt, help a great deal in locating the overseas Indian contribution to the evolution of many countries of the world of which overseas Indians are, and have always been, an integral part.

Total Users : 2297

Total Users : 2297